Seppe De Blust

Designing for real change

Seppe De Blust is a sociologist and urban designer. After working in between politics and policy, he co-founded endeavour, an Antwerp based office for socio-spatial research. Seppe conducted his PhD research in Architecture at the KU Leuven with a strong focus on the position of critical spatial practitioners in processes of urban transformation. At the NEWROPE chair Seppe leads the action research on reflexive pedagogies, collective learning in action and intervention driven design.

In 2019 Seppe obtained a PhD from the Faculty of Engineering Science at KU Leuven. His research dissertation was titled ‘Creating room for socially innovative planning practice under post-political conditions - A metareflexive action research on the daily struggles of a transformative planning office’ (find a download-link at the end of this interview).

In this interview, with NEWROPE program lead Michiel van Iersel, he reflects on his work as a sociologist in the field of urban design and on the importance of collective learning and action as ways to develop more open, critical and reflective approaches to how we shape our environments.

The estimated time to read this interview is 15-17 minutes.

Michiel van Iersel (MI)

The office you are referring to in the title of your dissertation is your own practice, endeavour, which you started in Antwerp with your friends and fellow PhD students Maarten Desmet and Tim Devos back in 2014 and for which you use “Hack the City” as your slogan. Could you talk a bit about the philosophy behind endeavour and how these ideas and your work relate to the field of (urban) design?

Seppe de Blust (SB)

It all started with the idea to strengthen the relation between the social sciences and design, This was based on different experiences we had as young practitioners trying to make sense of the role of design, planning and urban policy in everyday reality. We had the feeling that urban design was operating in a kind of vacuum, instrumentalized by different societal agendas (from the competition between cities to a car oriented perspective on housing) without sufficiently using its critical capacity to question how we are living and working today and how we could use spatial development to change certain societal attitudes, address local needs or include unheard voices.

I remember how I was puzzled by the absence of a strategic and political insight at the architectural office I worked after I stopped as an active politician (as a member of the city council of Antwerp in Belgium). There was an immense gap between the good intentions behind a lot of the urban strategies developed in that office and the way they were discussed or negotiated on a political level, as if controlling the costs and the narrative were the only arguments left standing. How can you - as a designer - be more strategic, take a position and find the right means to relate, strengthen or confront existing social and political discussions?

We had the feeling that urban design often had the role of organising and stabilising a given society and our living environment instead of triggering new ideas and becoming an active agent in reshaping the city. As children of the European optimism of the early nineties we were confronted with the social and financial crises that hit Europe after 2008 and at the same time sensed a complete lack of critical change.

With our office we tried to search again for the conditions that could allow design, and all the people that in one way or another are part of an urban design process, to speak up and explore new ways of developing the city collectively. Not as a new, government-led, participatory process but as an active endeavour to redefine the position of the designer. And as a way to develop new methods and tools to translate knowledge and collaborate with a variety of voices. And, most importantly, to develop a critical attitude to evaluate the outcome of design and go beyond good intentions.

From the first day we believed that finding this position needed a stronger balance between architecture and social sciences. Where two of the three founders of endeavour were trained as architects, I had a background in sociology. Combining those expertises helped to become part of both worlds. In order to keep this position as a mediator one of our first decisions was not to design. Up until today we have kept that promise. Although it is often tempting to start designing, this initial choice helped to develop a clear identity and pushed us to discover alternative ways to directly intervene, from campaigning, coaching and developing digital tools to launching our own centre for debate in Antwerp, called Stadsform.

MI

What made you decide to combine the development of your own practice with the pursuit of a PhD? What is the importance and influence of research in your work and vice versa?

SB

My research on finding the room to manoeuvre for critical spatial practices relates back to the possibility to eventually build critical capacity in order to have the means to respond more directly to changing circumstances, but also the skills to anticipate and activate opportunities for change.In terms of research methods there is no better way than approaching it through a process of trial-and-error. This was the reason why we started endeavour and I chose to engage with it as an action researcher. Establishing the office to actively challenge the urban design culture in Flanders, which back then was mostly focussed on masterplanning. Research helped to create the framing or critical mirror to better understand the consequences of our actions but also ways to develop new tools and organisational structures. The office on the other hand gave me a direct entrance into multiple case study and became the economic and collaborative backbone of my PhD. To combine research and practice is, I think, essential for urban design to avoid or foresee the risk of being co-opted by certain political or economic interests. You can start with good intentions, but if your work is not rooted in research it runs the risk of legitimizing and reinforcing a dominant way of imagining and shaping our cities.

We wrote an article on what we called ‘strategic ambiguity’, and the question how to build up a certain critical capacity without losing the possibility to actively engage in a large variety of projects. And while we were reflecting on the notion of strategic ambiguity, or the idea to strategically use unclarity in order to get access to certain networks, we were invited to give a lecture at the ETH in March 2017 for a lecture series of Marc Angélil. This lecture focussed a lot on openness or transparency, an ethos that is in direct conflict with ambiguity and unclarity. A reflection on this tension eventually resulted in a stronger focus on the internal structure of endeavour as a workers cooperative, a legal structure that gave us both the flexibility to operate under different forms and experiment with different kinds of output while providing us with the financial stability to continue our practice.

This understanding of how one can translate certain principles in such a way that they not only steer your methodologies, but are also reflected in the way you organise yourself and in the way you collaborate with others and how you talk and discover the world, are key to my PhD and still key to my current research interests. And this understanding is what I would love to contribute to young architects and urban designers that are starting to draft their own career path, and discover their own fields of action.

MI

You use various concepts to describe the work of endeavour, such as metareflexive action research, transformative and socially innovative planning and the post-political. Could you elaborate on these key concepts and illustrate them with an example from your own work?

SB

All these concepts are highly interrelated. Let’s start with the post-political and go back from there. We use ‘Post-political’ to describe a condition where methods of planning or design have the intention to be part of democratic practice, but are often delusional, overruled by power games without even noticing. Or more specifically, design starts to legitimize the absence of real debate. I was confronted with this problem for the first time in the architectural office I worked for before we started endeavour. Within that office it seemed that we often forgot to think strategically and reflect on the impact of our proposals. There was a clear absence of vocabulary or tools to rethink our own agency. We started each project with a similar design methodology, which to me seemed so counter-intuitive knowing that each project is part of different local debates, has a different symbolic value and is related to different stakes. If you want to deal with this it becomes important to understand these different conditions and critically and creatively work with them.

Social innovation can help in this respect. Already dating back to the early 80’s and even before, social innovation has as its main ambition to tackle the dominance of established practices by organising parallel trajectoires of collective action, working with local communities to empower them while directly addressing local needs. I was always triggered by this approach and believed in the power of local initiatives to, in the end, challenge larger structures. At the same time I wondered how you can deal with this as a designer and integrate it in an architectural practice. How can you make it part of amore mainstream societal position by providing services (designing buildings, making plans) and by becoming part of networks with others who often have a much stronger societal or economic position, such as (local) governments or developers. If you would compare this with, for instance, graphic design, architecture is more risk-averse. It provides a service that, partly because of the high costs of construction and the financial risks that come with it, inherently seeks to confirm rather than to question dominant perspectives.

Transformative practice became my way to deal with this question of critical agency. Taking the relational and indirect aspect of social innovation more seriously (focussed on empowerment and structurally changing networks of power and decision making). Instead of only focussing on local needs I started to get more and more interested in the idea that design could provide the right conditions for others to get empowered or to feel liberated in order to act. How to design that it triggers administrations and local citizens to organise themselves differently, take new roles and as such have a longer lasting impact? In endeavour this often meant that instead of making a master plan we were more starting to activate and organise new organisational structures, new ways of working together and as such rethink ownership structures or decision making procedures that form the core elements of urban transformation. I remember a project we did together with 51N4E on the dry docks in Antwerp. We wanted to create a masterplan to revitalize the area while creating the right conditions for social economy organisations (a.o. Restoration of heritage) to become an active partner in the area. Instead of a masterplan we wrote a manual for revitalization, tried (and failed) to set-up a new organisation between cultural and social economy partners to curate the site and proposed to rethink the procedure of the city on concessions in order to give non-market driven companies an opportunity to compete.

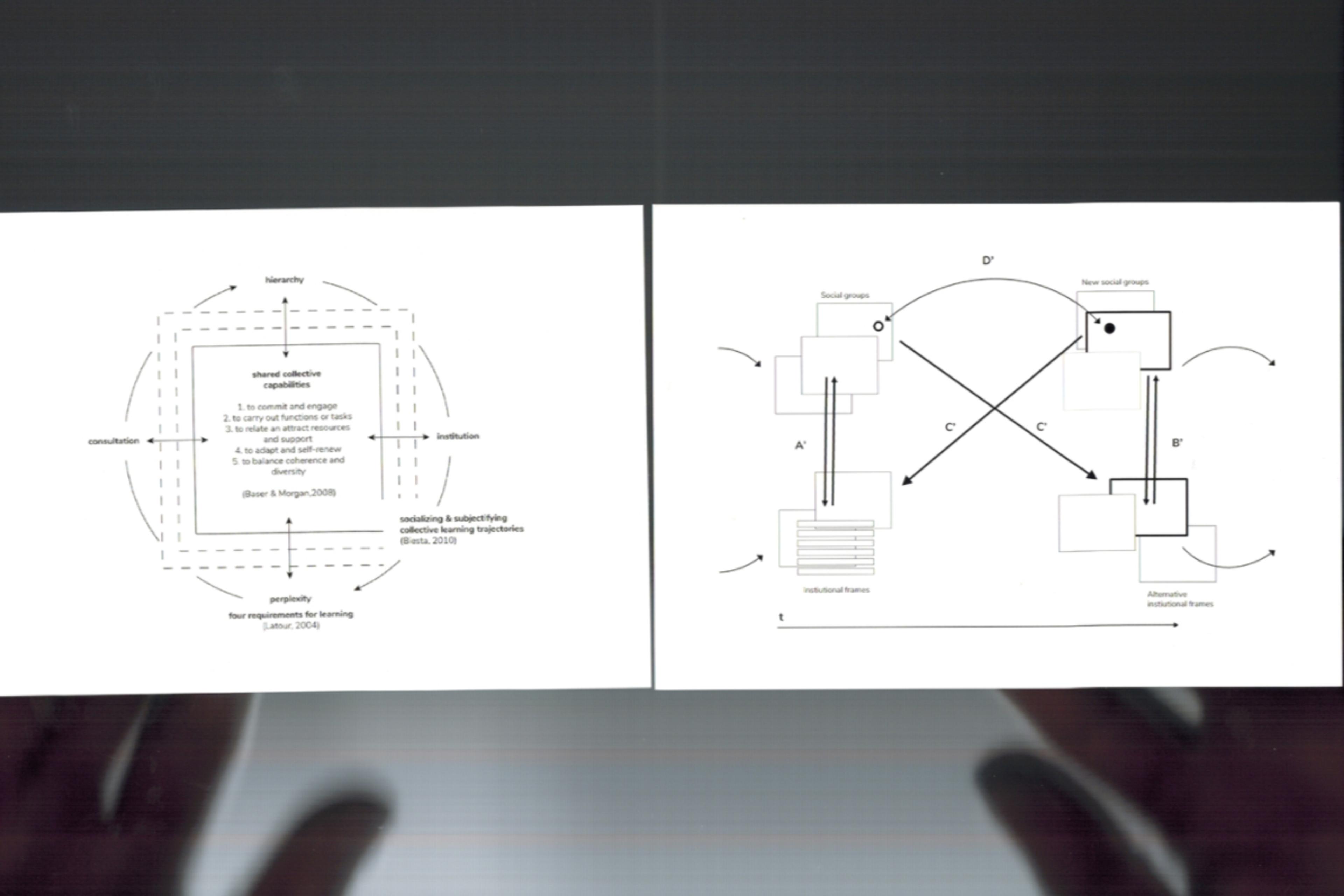

This switch to a more organisational logic brings us to metareflexive action where I try to advocate and develop a method in my PhD that allows you as a designer to develop your own agency and organise yourself in such a way that you can be flexible enough to navigate opportunities and in the meantime build enough critical network and reflection to strengthen impact, without becoming too dependent on others. I start here from the idea that "scientists are embodied minds, i.e. people whose thoughts and interests are intertwined and shaped by their place of birth, what they’ve seen, touched, smelled, the people they’ve interacted with etc. And that in order to activate this rich experience and rich ground for reflexivity we need to create the right conditions and expectations to operate.

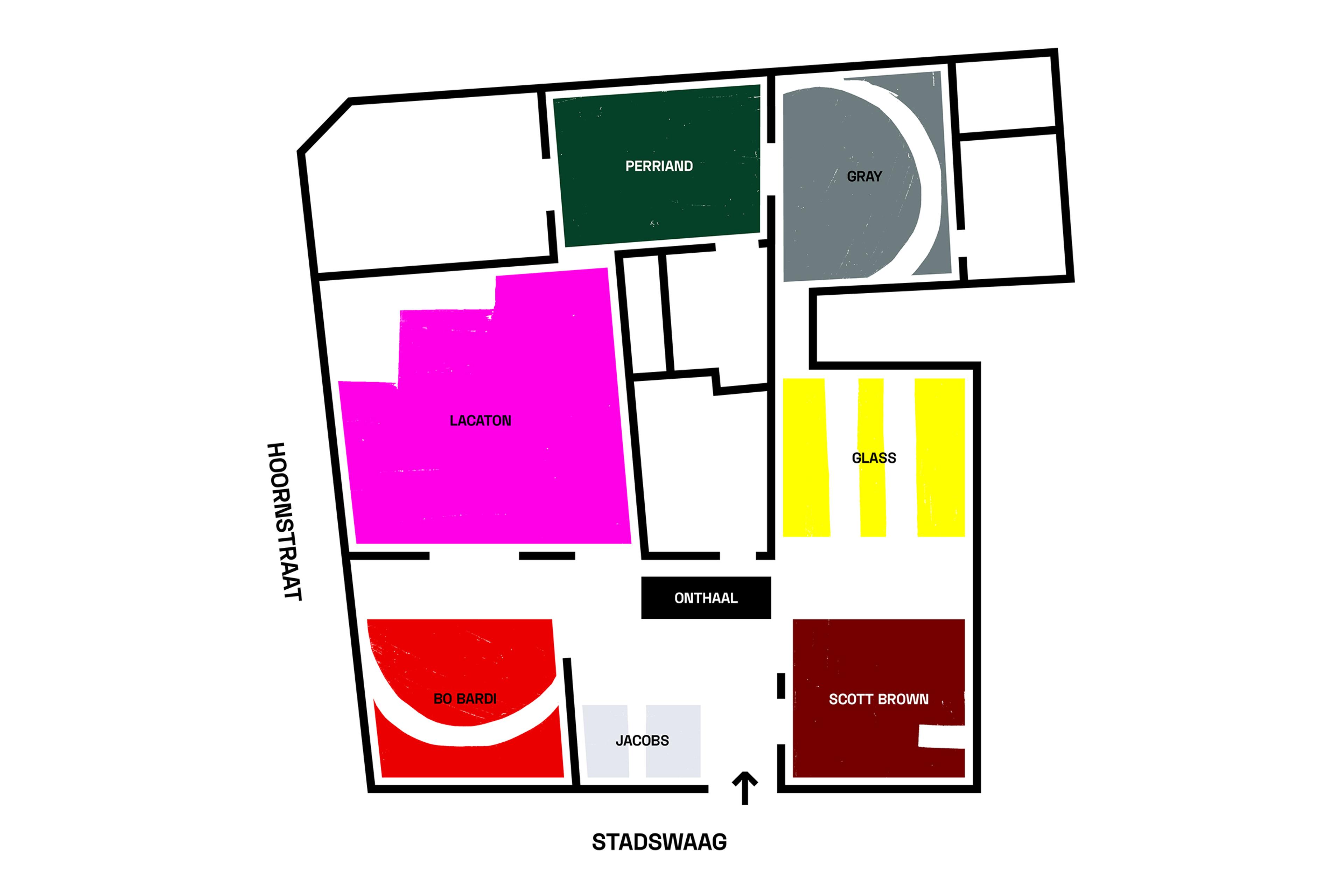

With endeavour this resulted in a workers cooperative where we avoided the market impact by introducing certain economic logics, for example by not counting hours, everybody working at endeavour for more than three years becomes a partner without extra investment, etc..We also apply logics of personal development, where we give team members the possibility to explore new capacities and involve personal research in their work. As an office we invest in our own self-initiated, often unpaid projects where we explore new fields of action. This work often counts for 20-30% of our time and consists, for instance, of helping civil movements with expressing their spatial claims and curating our own center for dialogue and the city Stadsform. It occupies the ground floor of a building in the centre of Antwerp that can be used during the day by co-workers and neighbours and in the evening stages discussions on urgent urban (design) topics such as health, religion, labour and digitisation.

MI

In your dissertation you are suggesting that planners are free agents that open the possibility for others to engage in such a way that actors who are typically outside of the political system, to paraphrase Parkers and others, "appear on the stage of social design". How does this relate to the often repeated claim that designers and planners have to become more inclusive and create more democratic participatory design processes?

SB

The idea of a more inclusive and democratic participatory design starts from a strong belief in a deliberate form of democracy or in democratic politics as the inclusive deliberation between all stakeholders, in which reasoning is based on well-founded arguments and the absence of coercion. I think with endeavour, we love to believe that this is true. At the same time we realise that this is often not the case and as urban designers we should avoid to take this form of politics for granted.

Over the years we introduced a more disruptive or even agonistic understanding of democracy in our practice. It starts from the idea that the competition for power and influence will always be part of the debate and that in order to introduce new ideas it is important to disrupt the existing societal order. In our practice this plays out by radically reinterpreting the output of projects and our own agency, which is more and more focussed on creating the room for others to reconsider their position. For instance by proposing an alternative ownership structure as part of a master planning process or by asking civil actors to take over the final editing of the consultancy project and, as such, the powerful position of authorship.

This approach asks you to constantly navigate and reflect and understand the game you’re working in, trying to identify cracks in different systems and find opportunities for positive change. For instance, with neighbourhood plans we often have the feeling that everything is already so well organised that there is no space to question things. Organising inclusive processes as a designer in these kind of projects can maybe ease your conscience for a while, but won’t have a direct impact on the programme and logics driving the development. Understanding these constraints and limits of critical actions made us realise over the years that we had to switch our focus to more unstable fields of urban transformation. such as new energy landscapes, alternative housing models, land restoration and cultural diversity.

MI

What are some of the lessons you learned through your research about ways in which we can move from values and knowledge to meaningful actions, as you are suggesting in your dissertation? What are some of the methods, or tips and tricks, we can all benefit from?

SB

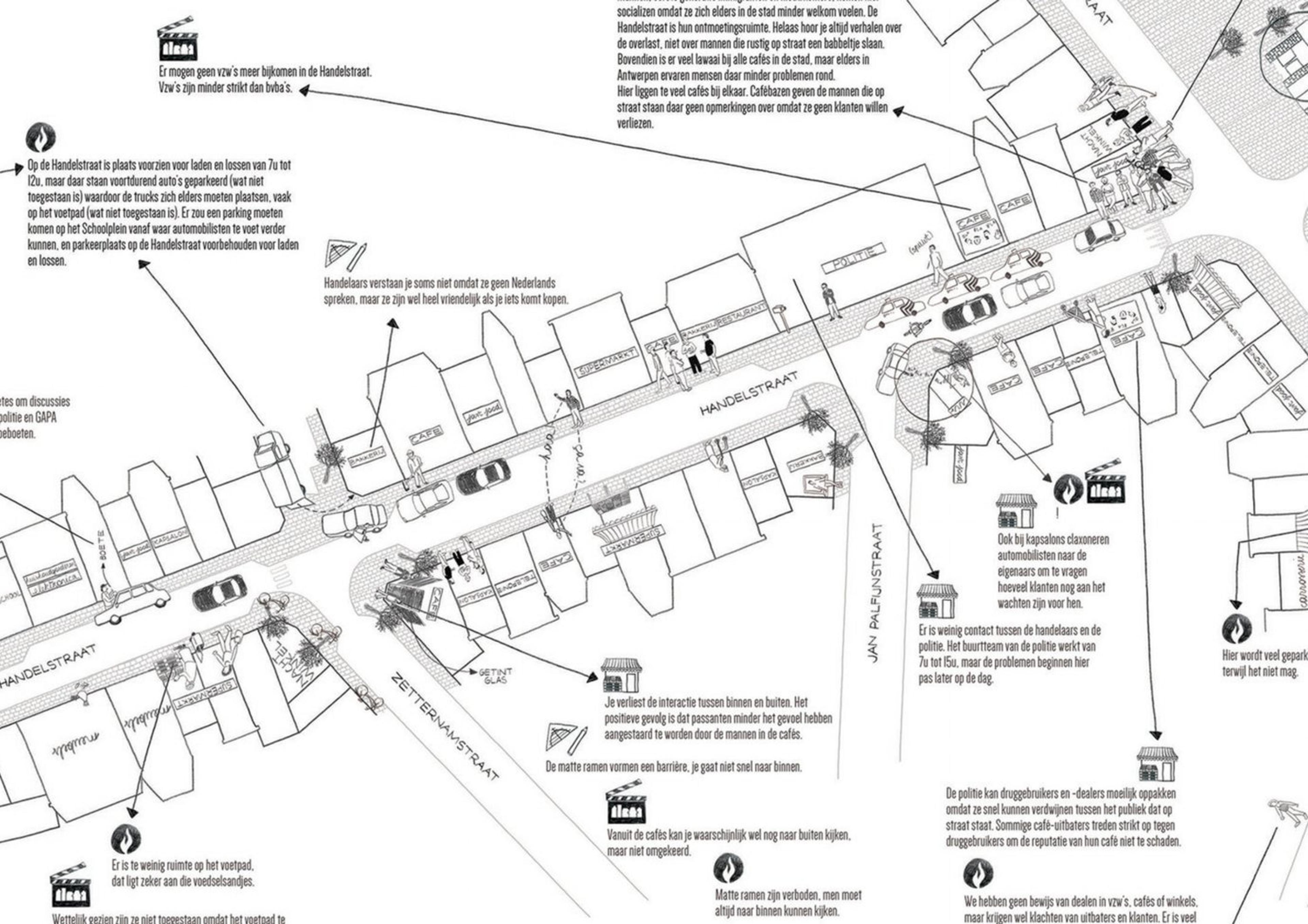

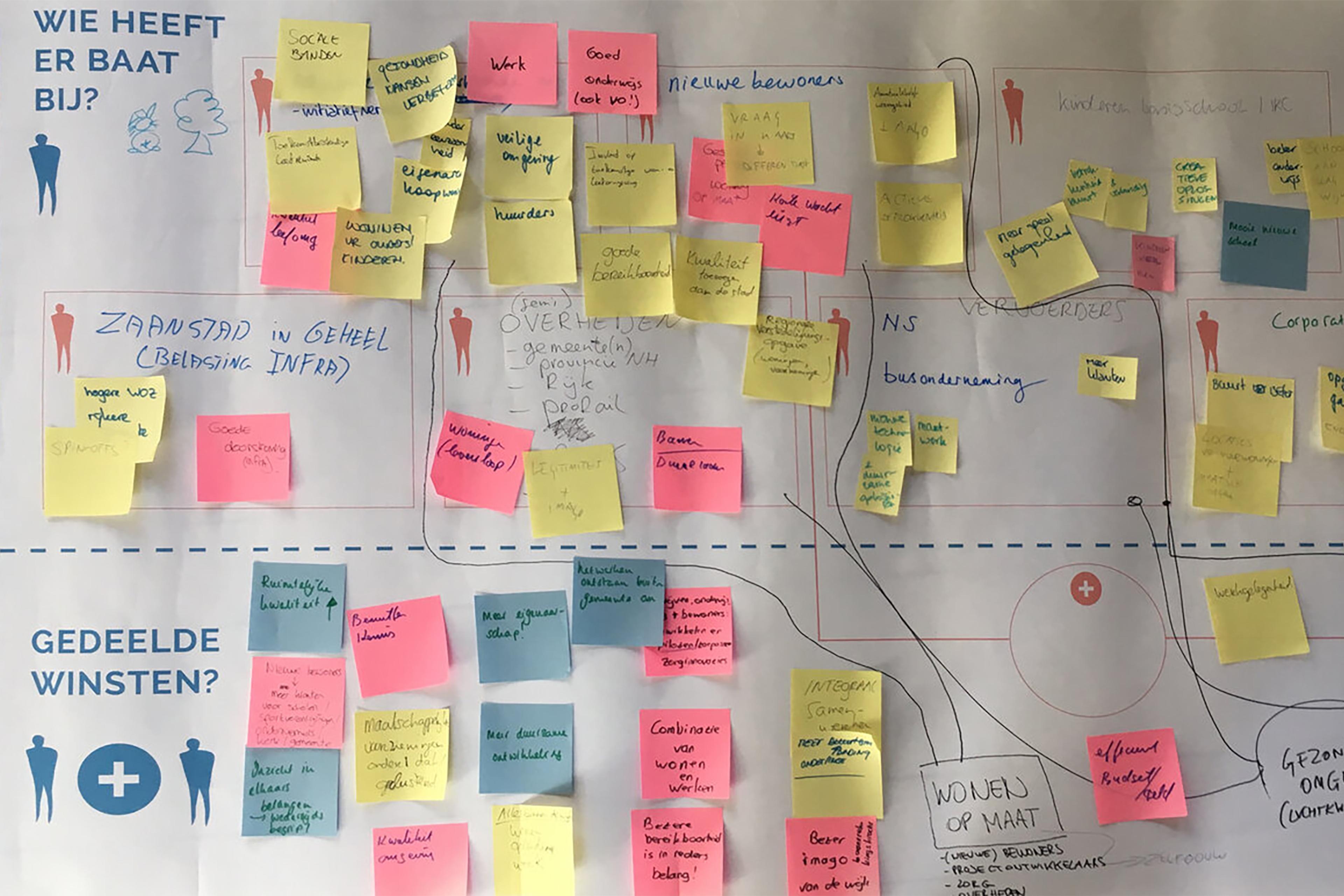

I think the first one is the design of shared carriers for knowledge. In all our projects we try to engage with local actors, from citizens to activists, developers and civil servants. We approach them on the basis of their specific (intangible) expertise. Designing a format (whether its a conversation series, a physical map, digital platform or new collaborative structure). This becomes the first move to bring all the expertise and the different interpretations to the table and find opportunities for change. You’ll never have such a rich debate when you involve actors based merely on the formal position they represent.

Our first commissioned project was on the perception of safety in public space. For one of the cases we made a drawing of different phenomena we traced during different days and nights of our observation. With this drawing we went to different shop owners, the police, youth workers and asked them to map their interpretation of what we observed. We added all those interpretations to the drawing and used this to have a first group discussion. Giving everyone in the room the possibility to reflect on different (and their own) interpretations and opinions, instead of using their time to propose something or make a claim, resulted in such a rich discussion and directly showed the communicative and synthesizing qualities of design as a medium that can be exact and playful at the same time.

A second one could be the idea that it is important to find ways to include specific values in the whole operation of the architectural practice. As endeavour we could only develop actions that were in line with our values because everything we did, from our (internal) communication and human resource policy to the way we structure our bookkeeping is organised to support our core values and create the right conditions for critical agency. Of course this process takes a while and is always in the making.

With endeavour we chose to strengthen our critical capacity by focussing our attention on becoming a platform for others. Instead of claiming a certain expertise or representational position (which would be highly problematic in our case, today formed as a rather homogenous group of ten white middle class individuals) we worked hard to redefine the expectations of an urban transformation process. In every assignment we create the right conditions for others to become the experts of their own trajectory and challenge the expectations of those in power.

As endeavour we found an interesting balance over the last years of being a critical in- and outsider of the Flemisch spatial planning scene. Confirming on the one hand to what you may expect from a classical planning office, while also challenging certain mechanisms in a rather fundamental way. For instance by questioning the output of a design process and by always working in dialogue). Over the next few years it will be very important to keep on questioning this balance. Now that we found a structure to create enough freedom to act in a critical manner it is maybe the right moment to start questioning our own internal diversity as an office.

MI

You argue that the framework for planning and action research that you propose in your research is capable of orchestrating complex processes of socio-spatial transformation. Could you speculate on an ideal transformation process, and the role of design(ers) in it?

SB

Even to suggest an ideal transformation process is probably taking the wrong direction and would keep control in the centre of urban design. So let’s start to acknowledge as designers that we don’t have things under control (and we shouldn’t), but that we use the time that is given to us by society to respond in a very precise way to changing conditions. And that each of these responses has the ultimate aim to strengthen our collective capacity to co-exist.

MI

How are you applying your research in the context of the NEWROPE Chair and ETH? How is it connected to the projects you are currently working on and (how) are you trying to connect it to the education and work of architecture students who participate in studios?

SB

I think my work played a role in how we established the chair and more specifically the design studio with a strong focus on collaboration and positionality. In the next few years we will try to bring these principles back to practice not only with a new publication on design in dialogue but also by launching a new programme on the idea of - what we call - ‘adaptive infrastructure’.

With this programme we don’t try to get a perfect grasp of the state of infrastructure in Europe or start to compare exemplary projects of adaptive infrastructure, but try to unravel how we can create the right local conditions in order for a city and its citizens to dare take up its infrastructural questions while encouraging future designers to find ways to engage with this complex field.

Infrastructure seems to be the field par excellence where on the one hand dominant practices are still in control of the whole development process and on the other hand new uncertainties are destabilizing this process of power & control. Bringing infrastructure back to the heart of urban design practice, and see it as something dynamic and not static, would create a certain sense of urgency to engage with more open, critical and reflective approaches to design practice.